This article is part of the Códice de Algodón project by Pima Prima®—a cultural and historical journey through the roots, rituals and relevance of Peruvian cotton from antiquity to today

Across the highlands and coastlines of Peru, an ancient rhythm continues—the click of a backstrap loom, the interlacing of warp and weft, the hands of artisans weaving stories into fabric. For thousands of years, weaving has been at the heart of Andean life, a sacred art form passed from generation to generation. Today, these time-honored techniques are not only surviving—they are thriving, finding new life in the global fashion scene.

As modern designers seek sustainable, meaningful alternatives to fast fashion, they are turning to ancient practices for inspiration and integrity. In this revival, the art of weaving stands as a bridge between the ancestral and the contemporary, shaping a future where fashion is as conscious as it is beautiful.

Ancient Techniques with Timeless Value

The Andean region has long been known for its sophisticated textile traditions, cultivated by civilizations like the Paracas, Nazca, Wari, and Inca. Among the most enduring and revered techniques are the backstrap loom and double-cloth weaving—methods that remain remarkably intact thanks to the dedication of skilled artisans.

The Backstrap Loom

This portable loom, simple in design yet profound in cultural weight, consists of wooden rods, thread, and a strap worn around the weaver’s waist. The artisan becomes part of the loom itself—anchoring one end of the warp to a tree or post, and the other to their body. Weaving becomes a physical and spiritual dialogue between the weaver, the earth, and the threads.

The technique allows for astonishing precision and complexity, resulting in textiles that are not only functional but deeply symbolic. Patterns passed down through generations depict sacred animals, geographic features, and stories encoded in thread. Scarves, belts, and tapestry panels made on the backstrap loom are living maps of cultural identity.

Double-Cloth Weaving

One of the most technically advanced methods developed in pre-Columbian America, double-cloth weaving involves weaving two layers of cloth simultaneously. The result is a reversible textile, often with contrasting patterns and colors on each side.

Beyond its impressive craftsmanship, this technique holds symbolic meaning in Andean cosmology—expressing duality, complementarity, and harmony. Each side of the textile represents a mirror of the other, much like the Andean understanding of balance between worlds: the upper (hanan) and lower (hurin), the spiritual and the material.

Legend in the Loom: Myth and Meaning

Weaving in the Andes is not only technique—it is myth. According to legend, the first weaver was taught by a sacred spider, or ñañakaq—a divine creature believed to have descended from the heavens to teach humanity how to spin and weave the fibers of the earth. In some Quechua and Aymara oral traditions, weaving is said to have been gifted by the moon goddess Mama Quilla, who passed the knowledge on to women so they could connect with nature and preserve memory through fabric.

Each textile, therefore, carries not just design, but destiny. The symbols that dance across the warp and weft are not decorative—they are a language. A condor might represent the upper world, a spiral the path of time, and stepped motifs the sacred mountains (apus). The weaver becomes a kind of priestess or guardian, translating cosmology into cloth.

These legends persist not in books, but in hands—hands that remember the rhythms of their ancestors, the teachings of myth, and the sacred responsibility of their craft.

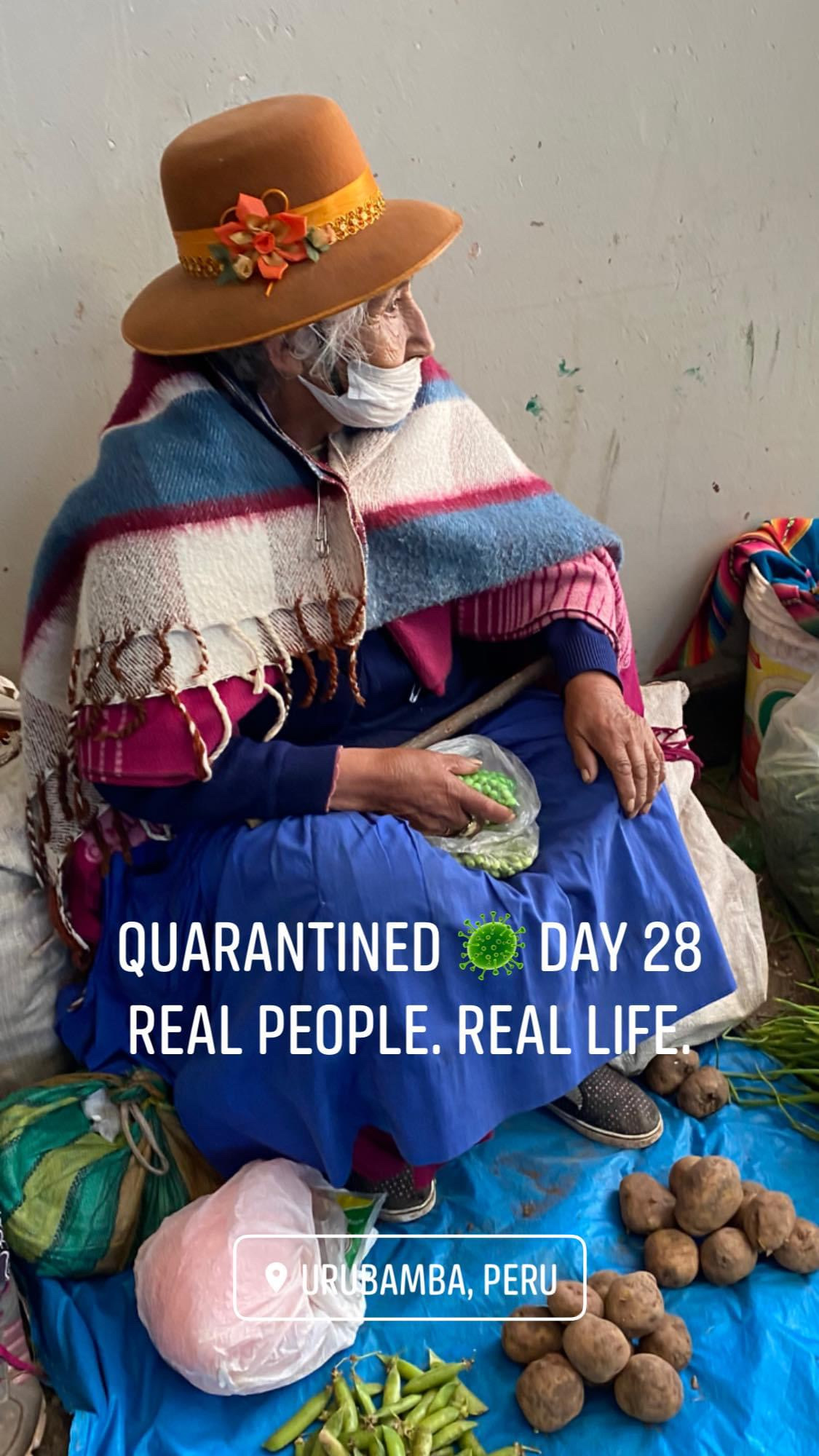

Guardians of Tradition: The Role of Artisans

Behind every handwoven textile is an artisan—a guardian of cultural memory, a storyteller in thread. In rural regions of Peru, particularly in communities in Cusco, Ayacucho, and Puno, generations of weavers have preserved these techniques through patient mentorship and daily practice.

Weaving is often learned through quiet observation: children watch elders at the loom, mimic their movements, and gradually take on more complex designs. The process is immersive, meditative, and inherently communal.

Each pattern woven into the fabric carries significance—depicting local landscapes, cosmological beliefs, and familial lineages. In this way, the textile becomes a vessel of history, a wearable form of resistance and resilience.

Today, thanks to growing interest from ethical fashion movements and support from cooperatives and nonprofits, these artisans are finding new platforms to share their work. Their craft is gaining international recognition, not as a trend, but as a cultural treasure.

A Source of Inspiration: Influence on Modern Designers

As the fashion industry confronts the urgent need for sustainability, more designers are shifting from speed and volume to values and meaning. This shift has led many to the Andes—not just for the visual richness of its textiles, but for the worldview woven into every thread.

Brands like Pima Prima® are leading the charge from within, blending traditional methods with modern silhouettes and luxury fibers like ELS Pima cotton. The result is a fusion of past and present, heritage and innovation.

This is not cultural appropriation—it’s cultural collaboration. A meaningful exchange where artisans gain visibility and income, and designers gain access to centuries-old knowledge systems that challenge the wasteful norms of industrial fashion.

Weaving the Future, One Strand at a Time

The resurgence of ancient weaving techniques in modern fashion is more than a nostalgic gesture—it is a powerful act of cultural preservation, environmental stewardship, and creative reinvention.

At a time when the fashion world is reckoning with overproduction, pollution, and exploitation, the lessons embedded in Andean weaving offer a different path. A path that honors the artisan’s hand, the rhythm of the loom, and the deep relationship between fabric and the land it comes from.

By celebrating the art of weaving, we are not only honoring the skill of individual weavers but also reimagining fashion as a tool for storytelling, resistance, and renewal.

The threads of the past are not just relics—they are the fibers of the future. And in the looms of the Andes, guided by memory, myth, and mastery, the fabric of that future is being woven, one strand at a time.